Art Final Quizlet Great Stupa India Picture Angkor Wat Cambodia

Ōṃ (or Aum ) ( ![]() mind(help·info) ; Sanskrit: ॐ, ओम्, romanized: Ōṃ ) is the sound of a sacred spiritual symbol in Indic religions. The significant and connotations of Om vary between the diverse schools within and across the various traditions. It is role of the iconography constitute in ancient and medieval era manuscripts, temples, monasteries, and spiritual retreats in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism.[1] [2] As a syllable, it is often chanted either independently or before a spiritual recitation and during meditation in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.[3] [4]

mind(help·info) ; Sanskrit: ॐ, ओम्, romanized: Ōṃ ) is the sound of a sacred spiritual symbol in Indic religions. The significant and connotations of Om vary between the diverse schools within and across the various traditions. It is role of the iconography constitute in ancient and medieval era manuscripts, temples, monasteries, and spiritual retreats in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism.[1] [2] As a syllable, it is often chanted either independently or before a spiritual recitation and during meditation in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.[3] [4]

In Hinduism, wherein it signifies the essence of the Ultimate Reality (parabrahman) which is consciousness (paramatman),[v] [six] [vii] Om is one of the most important spiritual symbols.[eight] [ix] It refers to Atman (Self within) and Brahman (ultimate reality, entirety of the universe, truth, divine, supreme spirit, cosmic principles, noesis).[10] [11] [12] The syllable is ofttimes found at the beginning and the finish of capacity in the Vedas, the Upanishads, and other Hindu texts.[12] It is a sacred spiritual incantation fabricated before and during the recitation of spiritual texts, during puja and private prayers, in ceremonies of rites of passage (sanskara) such as weddings, and during meditative and spiritual activities such equally Pranava yoga.[13] [14]

The syllable Om is also referred to as Onkara/Omkara and Pranav/Pranava amidst many other names.[15] [sixteen]

Common names and synonyms [edit]

The syllable Om is referred to by many names, including:

- Praṇava ( प्रणव ); literally, "fore-sound", referring to Om as the earliest sound.[17] [18]

- Oṅkāra ( ओङ्कार ) or oṃkāra ( ओंकार ); literally, "Om-maker", cogent the first source of the audio Om and connoting the human activity of creation.[19] [20] [21] [22]

- Ik Oṅkār ( ਇੱਕ ਓਅੰਕਾਰ ); literally, "1 Om-maker", and an epithet of God in Sikhism. (see below)

- Udgītha ( उद्गीथ ); meaning "song, dirge", a word found in Samaveda and bhasya (commentaries) based on it, which is also used equally a name of the syllable.[23]

- Akṣara ( अक्षर ); literally, "imperishable, immutable", and also "letter of the alphabet" or "syllable".

- Ekākṣara ; literally, "one letter of the alphabet", referring to its representation as a single ligature. (see below)

Origin and meaning [edit]

The etymological origins of ōm/āum have long been discussed and disputed, with even the Upanishads having proposed multiple Sanskrit etymologies for āum, including: from "ām" ( आम् ; "yep"), from "ávam" ( आवम् ; "that, thus, yes"), and from the Sanskrit roots "āv-" ( अव् ; "to urge") or "āp-" ( आप् ; "to attain").[24] [A] In 1889, Maurice Blumfield proposed an origin from a Proto-Indo-European introductory particle "*au" with a function similar to the Sanskrit particle "atha" ( अथ ).[24] Still, contemporary Indologist Asko Parpola proposes a borrowing from Dravidian "*ām" meaning "'it is so', 'let it exist and so', 'aye'", a contraction of "*ākum", cognate with modern Tamil "ām" ( ஆம் ) significant "yes".[24] [25]

Regardless of its original meaning, the syllable Om evolves to hateful many abstract ideas fifty-fifty in the earliest Upanishads. Max Müller and other scholars state that these philosophical texts recommend Om as a "tool for meditation", explain various meanings that the syllable may be in the mind of ane meditating, ranging from "bogus and senseless" to "highest concepts such equally the cause of the Universe, essence of life, Brahman, Atman, and Self-knowledge".[26] [27]

The syllable Om is first mentioned in the Upanishads, the mystical texts associated with the Vedanta philosophy. It has variously been associated with concepts of "catholic audio" or "mystical syllable" or "affirmation to something divine", or as symbolism for abstract spiritual concepts in the Upanishads.[12] In the Aranyaka and the Brahmana layers of Vedic texts, the syllable is so widespread and linked to noesis, that it stands for the "whole of Veda".[12] The symbolic foundations of Om are repeatedly discussed in the oldest layers of the early Upanishads.[28] [29] The Aitareya Brahmana of Rig Veda, in section v.32, for example suggests that the 3 phonetic components of Om (a + u + m) correspond to the iii stages of cosmic creation, and when it is read or said, it celebrates the artistic powers of the universe.[12] [30] The Brahmana layer of Vedic texts equate Om with bhur-bhuvah-svah, the latter symbolising "the whole Veda". They offering diverse shades of significant to Om, such as it existence "the universe beyond the sun", or that which is "mysterious and inexhaustible", or "the space language, the infinite knowledge", or "essence of breath, life, everything that exists", or that "with which one is liberated".[12] The Samaveda, the poetical Veda, orthographically maps Om to the audible, the musical truths in its numerous variations (Oum, Aum, Ovā Ovā Ovā Um, etc.) and then attempts to extract musical meters from information technology.[12]

Pronunciation [edit]

When occurring within spoken Classical Sanskrit, the syllable is discipline to the normal rules of sandhi in Sanskrit grammer, with the additional peculiarity that the initial o of "Om" is the guṇa vowel grade of u, not the vṛddhi class, and is therefore pronounced equally a monophthong with a long vowel ( [oː]), ie. ōm not aum.[B] [31] Furthermore, the last m is often assimilated into the preceding vowel as nasalisation ( raṅga ). As a result, Om regularly pronounced [õː] in the context of Sanskrit.

However, this o reflects the older Vedic Sanskrit diphthong au, which at that stage in the language's history had not still monophthongised to o. This existence so, the syllable Om is ofttimes archaically considered every bit consisting of three phonemes: "a-u-thousand".[32] [33] [34] [35] Accordingly, some denominations maintain the primitive diphthong au viewing it to be more accurate and closer to the linguistic communication of the Vedas.

In the context of the Vedas, especially the Vedic Brahmanas, the vowel is often pluta ("three times equally long"), indicating a length of three morae ( trimātra ), that is, the fourth dimension it takes to say three calorie-free syllables. Additionally, a diphthong becomes pluta with the prolongation of its offset vowel.[31] When e and o undergo pluti they typically revert to the original diphthongs with the initial a prolonged,[36] realised as an overlong open back unrounded vowel (ā̄um or a3um [ɑːːum]). This extended duration is emphasised by denominations who regard it equally more than authentically Vedic, such as Arya Samaj.

All the same, Om is also attested in the Upanishads without pluta,[C] and many languages related to or influenced by Classical Sanskrit, such every bit Hindustani, share its pronunciation of Om ( [õː] or [oːm]).

Written representations [edit]

South asia [edit]

Statue depicting Shiva as the Nataraja dancing in a posture resembling the Devangari ligature for Om; Joseph Campbell argued that the Nataraja statue represents Om as a symbol of the entirety of "consciousness, universe" and "the bulletin that God is within a person and without"[37]

Om is represented in Devanagari as ओम् , equanimous of iv elements: the vowel letter of the alphabet आ ( ā ), the vowel diacritic े ( u ), the consonant letter म ( m ), and the virama stroke ् which indicates the absence of an implied final vowel. The syllable is sometimes written ओ३म् , notably by Arya Samaj, where ३ (i.e., the digit "3") explicitly indicates pluta ("iii times every bit long"; see in a higher place) which is otherwise only implied. For this same reason Om may too be written ओऽम् in languages such as Hindi, with the avagraha (ऽ) being used to point prolonging the vowel sound. (Nevertheless, this differs from the usage of the avagraha in Sanskrit, where it would instead bespeak the prodelision of the initial vowel.) Om may as well be written ओं , with an anusvara reflecting the pronunciation of [õː] in languages such as Hindi. In languages such equally Urdu and Sindhi Om may exist written اوم in Arabic script, although speakers of these languages may also use Devanagari representations.

The Om symbol, ॐ , is a cursive ligature in Devanagari, combining अ ( a ) with उ ( u ) and the chandrabindu (ँ, ṃ ). In Unicode, the symbol is encoded at U+0950 ॐ DEVANAGARI OM and at U+1F549 🕉 OM SYMBOL as a "generic symbol contained of Devanagari font".

In some South Asian writing systems, the Om symbol has been simplified farther. In Eastern Nagari Om is written only every bit ওঁ without an additional gyre. In languages such equally Bengali differences in pronunciation compared to Sanskrit have made the add-on of a curl for u redundant. Similarly, in Odia Om is written every bit ଓଁ without an additional diacritic. In languages using these writing systems, the letter for [oː] does resemble any other so Om would already exist read every bit [õː] equally written without any an additional curl.

Nagari or Devanagari representations are establish epigraphically on sculpture dating from Medieval Republic of india and on aboriginal coins in regional scripts throughout Southward Asia. In Sri Lanka, Anuradhapura era coins (dated from the 1st to fourth centuries) are embossed with Om forth with other symbols.[38]

There have been proposals that the Om syllable may already have had written representations in Brahmi script, dating to before the Common Era. A proposal by Deb (1848) held that the swastika is "a monogrammatic representation of the syllable Om, wherein 2 Brahmi /o/ characters ( U+11011 𑀑 BRAHMI Letter O) were superposed crosswise and the 'm' was represented by dot".[39] A commentary in Nature considers this theory questionable and unproven.[40] Roy (2011) proposed that Om was represented using the Brahmi symbols for "A", "U", and "Grand" (𑀅𑀉𑀫), and that this may have influenced the unusual epigraphical features of the symbol ॐ for Om.[41] [42]

East and Southeast Asia [edit]

The Om symbol, with epigraphical variations, is also found in many Southeast Asian countries.

In Southeast Asia, the Om symbol is widely conflated with that of the unalome; originally a representation of the Buddha's urna curl and later a symbol of the path to nirvana, information technology is a popular yantra in Southest Asia, particularly in Cambodia and Thailand. It frequently appears in sak yant religious tattoos, and has been a part of various flags and official emblems such as in the Thong Chom Klao of King Rama 4 ( r. 1851–1868)[43] and the present-day imperial arms of Cambodia.[44]

The Central khmer adopted the symbol since the 1st century during the Kingdom of Funan, where it is too seen on artefacts from Angkor Borei, one time the upper-case letter of Funan. The symbol is seen on numerous Khmer statues from Chenla to Khmer Empire periods and however in used until the present day.[45] [46] [ meliorate source needed ]

In Chinese characters, Om is typically transliterated as either 唵 (pinyin: ǎn ) or 嗡 (pinyin: ōng ).

Representation in various scripts [edit]

Northern Brahmic [edit]

Southern Brahmic [edit]

E Asian [edit]

Other [edit]

Hinduism [edit]

Om appears often in Hindu texts and scriptures, notably appearing in the first verse of the Rigveda[D]

In Hinduism, Om is one of the nigh important spiritual sounds.[8] [9] The syllable is frequently found at the beginning and the finish of capacity in the Vedas, the Upanishads, and other Hindu texts,[12] and is oftentimes chanted either independently or before a mantra, as a sacred spiritual incantation made before and during the recitation of spiritual texts, during puja and private prayers, in ceremonies of rites of passages (sanskara) such as weddings, and during meditative and spiritual activities such as yoga.[13] [fourteen]

It is the virtually sacred syllable symbol and mantra of Brahman,[47] which is the ultimate reality, consciousness or Atman (Self within).[10] [xi] [5] [6] [48]

It is called the Shabda Brahman (Brahman as sound) and believed to be the primordial sound (Pranava) of the universe.[49]

Vedas [edit]

Om came to be used as a standard utterance at the beginning of mantras, chants or citations taken from the Vedas. For instance, the Gayatri mantra, which consists of a poesy from the Rigveda Samhita (RV 3.62.ten), is prefixed not but by Om only by Om followed by the formula bhūr bhuvaḥ svaḥ.[l] Such recitations continue to be in employ in Hinduism, with many major incantations and ceremonial functions kickoff and ending with Om.[4]

Brahmanas [edit]

Aitareya Brahmana [edit]

The Aitareya Brahmana (7.18.xiii) explains Om as "an acquittance, melodic confirmation, something that gives momentum and free energy to a hymn".[8]

Om is the agreement (pratigara) with a hymn. Likewise is tathā = 'and so exist information technology' [the agreement] with a [worldly] song (gāthā) [= the applause]. Only Om is something divine, and tathā is something man.

—Aitareya Brahmana, seven.18.13[8]

Upanishads [edit]

Om is given many meanings and layers of symbolism in the Upanishads including "the sacred sound, the Yes!, the Vedas, the udgitha (song of the universe), the infinite, the all encompassing, the whole earth, the truth, the ultimate reality, the finest essence, the cause of the universe, the essence of life, the Brahman, the ātman , the vehicle of deepest knowledge, and self-cognition (atma jnana)".[27]

Chandogya Upanishad [edit]

The Chandogya Upanishad is i of the oldest Upanishads of Hinduism. It opens with the recommendation that "let a man meditate on Om".[51] It calls the syllable Om equally udgitha ( उद्गीथ ; song, chant), and asserts that the significance of the syllable is thus: the essence of all beings is earth, the essence of globe is water, the essence of h2o are the plants, the essence of plants is man, the essence of man is speech, the essence of speech is the Rigveda, the essence of the Rigveda is the Samaveda, and the essence of Samaveda is the udgitha (song, Om).[52]

Ṛc ( ऋच् ) is speech, states the text, and sāman ( सामन् ) is breath; they are pairs, and because they have love for each other, oral communication and breath observe themselves together and mate to produce a vocal.[51] [52] The highest song is Om, asserts department 1.1 of Chandogya Upanishad. It is the symbol of awe, of reverence, of threefold knowledge because Adhvaryu invokes it, the Hotr recites it, and Udgatr sings information technology.[52] [53]

The second volume of the first chapter continues its discussion of syllable Om, explaining its use as a struggle betwixt Devas (gods) and Asuras (demons).[54] Max Muller states that this struggle between gods and demons is considered allegorical past ancient Indian scholars, every bit skillful and evil inclinations inside man, respectively.[55] The legend in department 1.2 of Chandogya Upanishad states that gods took the Udgitha (song of Om) unto themselves, thinking, "with this vocal we shall overcome the demons".[56] The syllable Om is thus implied equally that which inspires the good inclinations within each person.[55] [56]

Chandogya Upanishad'due south exposition of syllable Om in its opening chapter combines etymological speculations, symbolism, metric structure and philosophical themes.[53] [57] In the second chapter of the Chandogya Upanishad, the meaning and significance of Om evolves into a philosophical discourse, such as in section 2.10 where Om is linked to the Highest Cocky,[58] and section 2.23 where the text asserts Om is the essence of three forms of noesis, Om is Brahman and "Om is all this [observed world]".[59]

Katha Upanishad [edit]

The Katha Upanishad is the legendary story of a lilliputian male child, Nachiketa, the son of sage Vājaśravasa , who meets Yama, the Vedic deity of death. Their conversation evolves to a discussion of the nature of man, cognition, Atman (Self) and moksha (liberation).[60] In section 1.2, Katha Upanishad characterises noesis ( vidyā ) as the pursuit of the good, and ignorance ( avidyā ) every bit the pursuit of the pleasant.[61] Information technology teaches that the essence of the Veda is to make man liberated and gratuitous, wait past what has happened and what has not happened, free from the past and the future, across good and evil, and one give-and-take for this essence is the word Om.[62]

The word which all the Vedas proclaim,

That which is expressed in every Tapas (penance, thrift, meditation),

That for which they live the life of a Brahmacharin,

Understand that word in its essence: Om! that is the discussion.

Aye, this syllable is Brahman,

This syllable is the highest.

He who knows that syllable,

Whatever he desires, is his.—Katha Upanishad 1.2.15-i.2.sixteen[62]

Maitri Upanishad [edit]

The Maitrayaniya Upanishad in sixth Prapathakas (lesson) discusses the meaning and significance of Om. The text asserts that Om represents Brahman-Atman. The iii roots of the syllable, states the Maitri Upanishad, are A + U + M.[63]

The sound is the body of Self, and it repeatedly manifests in three:

- as gender-endowed trunk – feminine, masculine, neuter;

- every bit light-endowed body – Agni, Vayu, and Aditya;

- equally deity-endowed body – Brahma, Rudra,[E] and Vishnu;

- equally mouth-endowed trunk – garhapatya, dakshinagni, and ahavaniya;[F]

- as knowledge-endowed torso – Rig, Saman, and Yajur;[Thousand]

- as world-endowed trunk – bhūr , bhuvaḥ , and svaḥ ;[H]

- as time-endowed body – past, present, and future;

- as heat-endowed body – jiff, burn, and Sunday;

- as growth-endowed body – nutrient, water, and Moon;

- as thought-endowed body – intellect, listen, and psyche.[63] [64]

Brahman exists in two forms – the fabric form, and the immaterial formless.[65] The cloth form is changing, unreal. The immaterial formless isn't irresolute, real. The immortal formless is truth, the truth is the Brahman, the Brahman is the light, the calorie-free is the Sun which is the syllable Om every bit the Self.[66] [67] [I]

The world is Om, its light is Sun, and the Sun is also the light of the syllable Om, asserts the Upanishad. Meditating on Om, is acknowledging and meditating on the Brahman-Atman (Self).[63]

Mundaka Upanishad [edit]

The Mundaka Upanishad in the second Mundakam (function), suggests the means to knowing the Atman and the Brahman are meditation, self-reflection, and introspection and that they can exist aided by the symbol Om.[69] [70]

That which is flaming, which is subtler than the subtle,

on which the worlds are gear up, and their inhabitants –

That is the indestructible Brahman.[J]

Information technology is life, it is speech, it is listen. That is the real. It is immortal.

Information technology is a mark to be penetrated. Penetrate It, my friend.Taking as a bow the great weapon of the Upanishad,

one should put upon it an arrow sharpened by meditation,

Stretching information technology with a thought directed to the essence of That,

Penetrate[Thousand] that Imperishable as the mark, my friend.Om is the bow, the arrow is the Self, Brahman the mark,

By the undistracted homo is Information technology to be penetrated,

Ane should come to exist in Information technology,

as the pointer becomes i with the mark.—Mundaka Upanishad 2.ii.2 – 2.2.four[71] [72]

Adi Shankara, in his review of the Mundaka Upanishad, states Om as a symbolism for Atman (Cocky).[73]

Mandukya Upanishad [edit]

The Mandukya Upanishad opens by declaring, "Om!, this syllable is this whole world".[74] Thereafter, information technology presents diverse explanations and theories on what it means and signifies.[75] This discussion is built on a structure of "four fourths" or "fourfold", derived from A + U + Yard + "silence" (or without an element).[74] [75]

- Om as all states of Time.

- In verse one, the Upanishad states that time is threefold: the by, the present and the future, that these three are Om. The four fourth of time is that which transcends time, that too is Om expressed.[75]

- Om as all states of Ātman .

- In verse 2, states the Upanishad, everything is Brahman, but Brahman is Atman (the Self), and that the Atman is fourfold.[74] Johnston summarizes these four states of Cocky, respectively, as seeking the concrete, seeking inner idea, seeking the causes and spiritual consciousness, and the fourth land is realizing oneness with the Self, the Eternal.[76]

- Om equally all states of Consciousness.

- In verses 3 to 6, the Mandukya Upanishad enumerates four states of consciousness: wakeful, dream, deep sleep, and the state of ekatma (existence 1 with Self, the oneness of Self).[75] These four are A + U + Thou + "without an chemical element" respectively.[75]

- Om as all of Knowledge.

- In verses 9 to 12, the Mandukya Upanishad enumerates fourfold etymological roots of the syllable Om. It states that the first element of Om is A, which is from Apti (obtaining, reaching) or from Adimatva (being showtime).[74] The 2d element is U, which is from Utkarsa (exaltation) or from Ubhayatva (intermediateness).[75] The tertiary element is M, from Miti (erecting, constructing) or from Mi Minati, or apīti (annihilation).[74] The fourth is without an chemical element, without development, beyond the area of universe. In this way, states the Upanishad, the syllable Om is indeed the Atman (the self).[74] [75]

Shvetashvatara Upanishad [edit]

The Shvetashvatara Upanishad, in verses 1.fourteen to 1.16, suggests meditating with the help of syllable Om, where one's perishable body is similar one fuel-stick and the syllable Om is the second fuel-stick, which with bailiwick and diligent rubbing of the sticks unleashes the concealed burn of thought and sensation within. Such noesis, asserts the Upanishad, is the goal of Upanishads.[77] [78] The text asserts that Om is a tool of meditation empowering one to know the God inside oneself, to realize one's Atman (Self).[79]

The Hindu deity Ganesha is sometimes referred to equally " oṃkārasvarūpa " (Omkara is his course) and used as the symbol for Upanishadic concept of Brahman.[80] [81]

Ganapati Upanishad [edit]

The Ganapati Upanishad asserts that Ganesha is same as Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, all deities, the universe, and Om.[82]

(O Lord Ganapati!) You are (the Trimurti) Brahma, Vishnu, and Mahesa. You are Indra. Yous are fire [Agni] and air [ Vāyu ]. You are the sunday [ Sūrya ] and the moon [Chandrama]. You are Brahman. Yous are (the three worlds) Bhuloka [earth], Antariksha-loka [infinite], and Swargaloka [heaven]. You lot are Om. (That is to say, You lot are all this).

—Gaṇapatya Atharvaśīrṣa 6[83]

Ramayana [edit]

In Valmiki's Ramayana, Rama is identified with Om, with Brahma proverb to Rama:

"You are the sacrificial performance. Y'all are the sacred syllable Vashat (on hearing which the Adhvaryu priest casts the oblation to a deity into the sacrificial fire). You are the mystic syllable OM. You are higher than the highest. People neither know your cease nor your origin nor who you are in reality. You appear in all created beings in the cattle and in brahmana south. Yous exist in all quarters, in the sky, in mountains and in rivers."

Bhagavad Gita [edit]

The Bhagavad Gita, in the Epic Mahabharata, mentions the meaning and significance of Om in several verses. According to Jeaneane Fowler, poesy 9.17 of the Bhagavad Gita synthesizes the competing dualistic and monist streams of thought in Hinduism, past using "Om which is the symbol for the indescribable, impersonal Brahman".[85]

"Of this universe, I am the Begetter; I am also the Mother, the Sustainer, and the Grandsire. I am the purifier, the goal of knowledge, the sacred syllable Om . I am the Ṛig Veda, Sāma Veda, and the Yajur Veda."

The significance of the sacred syllable in the Hindu traditions, is similarly highlighted in other verses of the Gita, such as poesy 17.24 where the importance of Om during prayers, charity and meditative practices is explained as follows:[87]

"Therefore, uttering Om, the acts of yagna (fire ritual), dāna (charity) and tapas (thrift) as enjoined in the scriptures, are ever begun by those who study the Brahman."

—Bhagavad Gita 17.24[87] [88]

Puranas [edit]

The medieval era texts of Hinduism, such as the Puranas adopt and aggrandize the concept of Om in their ain ways, and to their own theistic sects.

[edit]

The Vaishnava Garuda Purana equates the recitation of Om with obeisance to Vishnu.[89] According to the Vayu Purana, Om is the representation of the Hindu Trimurti, and represents the union of the iii gods, viz. A for Brahma, U for Vishnu and M for Shiva.[ citation needed ] The Bhagavata Purana (9.fourteen.46-48) identifies the Pranava every bit the root of all Vedic mantras, and describes the combined letters of a-u-m as an invocation of seminal birth, initiation, and the performance of sacrifice (yajña).[90]

Shaiva traditions [edit]

In Shaiva traditions, the Shiva Purana highlights the relation between deity Shiva and the Pranava or Om. Shiva is declared to exist Om, and that Om is Shiva.[91]

Shakta traditions [edit]

In the thealogy of Shakta traditions, Om connotes the female person divine energy, Adi Parashakti, represented in the Tridevi: A for the creative free energy (the Shakti of Brahma), Mahasaraswati, U for the preservative free energy (the Shakti of Vishnu), Mahalakshmi, and Thou for the subversive energy (the Shakti of Shiva), Mahakali. The twelfth volume of the Devi-Bhagavata Purana describes the Goddess every bit the mother of the Vedas, the Adya Shakti (cardinal energy, primordial ability), and the essence of the Gayatri mantra.[92] [93] [94]

Other texts [edit]

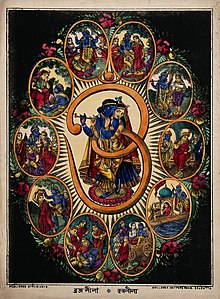

Radha and Krishna intertwined with an Om (

ওঁ) and surrounded by scenes from their life

Yoga Sutra [edit]

The aphoristic verse one.27 of Pantanjali'south Yogasutra links Om to Yoga practice, every bit follows:

तस्य वाचकः प्रणवः ॥२७॥

His word is Om.—Yogasutra 1.27[95]

Johnston states this verse highlights the importance of Om in the meditative practice of yoga, where it symbolises the 3 worlds in the Self; the iii times – past, present, and future eternity; the three divine powers – creation, preservation, and transformation in 1 Being; and iii essences in 1 Spirit – immortality, omniscience, and joy. Information technology is, asserts Johnston, a symbol for the perfected Spiritual Human.[95]

Chaitanya Charitamrita [edit]

In Krishnava traditions, Krishna is revered as Svayam Bhagavan, the Supreme Lord himself, and Om is interpreted in light of this. Co-ordinate to the Chaitanya Charitamrita, Om is the sound representation of the Supreme Lord. A is said to represent Bhagavan Krishna (Vishnu), U represents Srimati Radharani (Mahalakshmi), and Chiliad represents jiva, the Self of the devotee.[96] [97]

Jainism [edit]

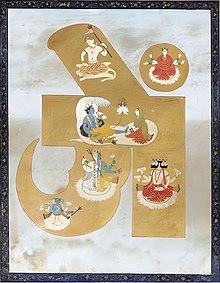

Painting illustrating the Jain Om symbol, from Jaipur, c. 1840

In Jainism, Om is considered a condensed form of reference to the Pañca-Parameṣṭhi past their initials A+A+A+U+M ( o3 m ).

The Dravyasamgraha quotes a Prakrit line:[98]

ओम एकाक्षर पञ्चपरमेष्ठिनामादिपम् तत्कथमिति चेत अरिहंता असरीरा आयरिया तह उवज्झाया मुणियां

Oma ekākṣara pañca-parameṣṭhi-nāmā-dipam tatkathamiti cheta "arihatā asarīrā āyariyā taha uvajjhāyā muṇiyā".

AAAUM [or merely "Om"] is the i syllable short class of the initials of the 5 supreme beings [pañca-parameṣṭhi]: "Arihant, Ashiri, Acharya, Upajjhaya, Muni".[99]

By extension, the Om symbol is likewise used in Jainism to represent the first five lines of the Namokar mantra,[100] the most important part of the daily prayer in the Jain religion, which honours the Pañca-Parameṣṭhi. These v lines are (in English): "(i.) veneration to the Arhats, (ii.) veneration to the perfect ones, (iii.) veneration to the masters, (4.) veneration to the teachers, (5.) veneration to all the monks in the globe".[98]

Buddhism [edit]

Om is frequently used in some later schools of Buddhism, for example Tibetan Buddhism, which was influenced past Indian Hinduism and Tantra.[101] [102]

In Due east Asian Buddhism, Om is oft transliterated as the Chinese grapheme 唵 (pinyin ǎn ) or 嗡 (pinyin ōng ).

Tibetan Buddhism and Vajrayana [edit]

The mantra om mani padme hum written in Tibetan script on the petals of a sacred lotus around the syllable hrih at the center; Om is written on the top petal in white

In Tibetan Buddhism, Om is often placed at the first of mantras and dharanis. Probably the most well known mantra is "Om mani padme hum", the six syllable mantra of the Bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteśvara. This mantra is particularly associated with the 4-armed Ṣaḍākṣarī grade of Avalokiteśvara. Moreover, every bit a seed syllable (Bīja mantra), Om is considered sacred and holy in Esoteric Buddhism.[103]

Some scholars interpret the commencement word of the mantra oṃ maṇi padme hūṃ to be auṃ , with a meaning similar to Hinduism – the totality of sound, existence, and consciousness.[104] [105]

Oṃ has been described past the 14th Dalai Lama equally "composed of three pure letters, A, U, and M. These symbolize the impure torso, oral communication, and mind of everyday unenlightened life of a practitioner; they also symbolize the pure exalted trunk, speech and mind of an aware Buddha".[106] [107] According to Simpkins, Om is a part of many mantras in Tibetan Buddhism and is a symbolism for wholeness, perfection, and the infinite.[108]

Japanese Buddhism [edit]

Nio statues in Kyoto prefecture of Nippon, are interpreted as proverb the start (open up mouth) and the end (airtight mouth) of syllable "AUM"[109] [110]

A-un [edit]

The term A-un ( 阿吽 ) is the transliteration in Japanese of the two syllables "a" and " hūṃ ", written in Devanagari as अहूँ. In Japanese, it is often conflated with the syllable Om. The original Sanskrit term is composed of two letters, the starting time (अ) and the concluding (ह) letters of the Devanagari abugida, with diacritics (including anusvara) on the latter indicating the "- ūṃ " of " hūṃ ". Together, they symbolically represent the beginning and the terminate of all things.[111] In Japanese Mikkyō Buddhism, the letters represent the beginning and the end of the universe.[112] This is comparable to Alpha and Omega, the start and last letters of the Greek alphabet, similarly adopted past Christianity to symbolise Christ as the first and stop of all.

The term a-un is used figuratively in some Japanese expressions as "a-united nations breathing" ( 阿吽の呼吸 , a-un no kokyū ) or "a-un relationship" ( 阿吽の仲 , a-un no naka ), indicating an inherently harmonious relationship or nonverbal communication.

Niō guardian kings and komainu king of beasts-dogs [edit]

The term is also used in Buddhist architecture and Shinto to depict the paired statues common in Japanese religious settings, most notably the Niō ( 仁王 ) and the komainu ( 狛犬 ).[111] I (usually on the right) has an open up mouth regarded by Buddhists as symbolically speaking the "A" syllable; the other (usually on the left) has a closed oral fissure, symbolically speaking the "Un" syllable. The two together are regarded as proverb "A-un". The general proper noun for statues with an open oral fissure is agyō ( 阿形 , lit. "a" shape), that for those with a airtight oral cavity ungyō ( 吽形 , lit. "'un' shape").[111]

Niō statues in Japan, and their equivalent in Eastern asia, announced in pairs in front of Buddhist temple gates and stupas, in the form of two vehement looking guardian kings (Vajrapani).[109] [110]

Komainu, besides called king of beasts-dogs, found in Japan, Korea and China, besides occur in pairs before Buddhist temples and public spaces, and once more, one has an open up rima oris (Agyō), the other closed (Ungyō).[113] [114] [115]

-

An ungyō komainu

-

An agyō komainu

-

Ungyō Niō at the Central Gate of Hōryū-ji

-

Agyō Niō at the Cardinal Gate of Hōryū-ji

Sikhism [edit]

Ik Onkar (Punjabi: ਇੱਕ ਓਅੰਕਾਰ; iconically represented as ੴ) are the first words of the Mul Mantar, which is the opening verse of the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh scripture.[116] Combining the numeral one ("Ik") and "Onkar", Ik Onkar literally means "i Om " ;[117] [L] these words are a statement that there is "ane God",[118] understood to refer to the "accented monotheistic unity of God"[116] and implying "singularity in spite of the seeming multiplicity of being".[119] [K]

Co-ordinate to Pashaura Singh, Onkar is used frequently equally invocation in Sikh scripture; it is the foundational word (shabad), the seed of Sikh scripture, and the basis of the "whole creation of time and infinite".[120]

Ik Onkar is a significant name of God in the Guru Granth Sahib and Gurbani, states Kohli, and occurs as "Aum" in the Upanishads and where information technology is understood every bit the abstruse representation of three worlds (Trailokya) of cosmos.[121] [N] Co-ordinate to Wazir Singh, Onkar is a "variation of Om (Aum) of the aboriginal Indian scriptures (with a change in its orthography), implying the unifying seed-force that evolves as the universe".[122] However, in Sikhism, Onkar is interpreted differently than in other Indian religions; Onkar refers straight to the creator of ultimate reality and consciousness, and not to the creation. Guru Nanak wrote a poem entitled Onkar in which, states Doniger, he "attributed the origin and sense of oral communication to the Divinity, who is thus the Om-maker".[116]

Onkar ('the Primal Sound') created Brahma, Onkar fashioned the consciousness,

From Onkar came mountains and ages, Onkar produced the Vedas,

By the grace of Onkar, people were saved through the divine give-and-take,

By the grace of Onkar, they were liberated through the teachings of the Guru.—Ramakali Dakkhani, Adi Granth 929-930, Translated by Pashaura Singh[120]

Thelema [edit]

For both symbolic and numerological reasons, Aleister Crowley adapted aum into a Thelemic magical formula, AUMGN, calculation a silent 'thou' (every bit in the word 'gnosis') and a nasal 'n' to the thousand to form the chemical compound letter 'MGN'; the 'g' makes explicit the silence previously simply implied by the terminal 'm' while the 'n' indicates nasal vocalisation connoting the breath of life and together they connote cognition and generation. Together these letters, MGN, have a numerological value of 93, a number with polysemic significance in Thelema. Om appears in this extended grade throughout Crowley'southward magical and philosophical writings, notably appearing in the Gnostic Mass. Crowley discusses its symbolism briefly in section F of Liber Samekh and in detail in chapter vii of Magick (Volume 4).[123] [124] [125] [126]

Modern reception [edit]

The Brahmic script Om-ligature has go widely recognized in Western counterculture since the 1960s, more often than not in its standard Devanagari form (ॐ), but the Tibetan alphabet Om (ༀ) has also gained limited currency in pop culture.[127]

In meditation [edit]

Meditating and chanting of Om can be washed past first concentrating on a picture of Om and then effortlessly mentally chanting the mantra. Meditating and mental chanting have been said[ past whom? ] to ameliorate the physiological state of the person past increasing alertness and sensory sensitivity.[128] [ unreliable source? ]

Notes [edit]

- ^ ॐ (U+0950)

- ^ ૐ (U+0AD0)

- ^ ओम् (U+0913 & U+092E & U+094D)

- ^ ওঁ (U+0993 & U+0981)

- ^ ੴ (U+0A74)

- ^ ꣽ (U+A8FD)

- ^ ᰣᰨᰵ (U+1C23 & U+1C28 & U+1C35)

- ^ ᤀᤥᤱ (U+1900 & U+1925 & U+1931)

- ^ ꫲ (U+AAF2)

- ^ 𑘌𑘽 (U+1160C & U+1163D)

- ^ ଓଁ (U+0B13 & U+0B01)

- ^ ଓଁ (U+0B13 & U+200D & U+0B01)

- ^ 𑑉 (U+11449)

- ^ 𑇄 (U+111C4)

- ^ 𑖌𑖼 (U+1158C & U+115BC)

- ^ 𑩐𑩖𑪖 (U+11A50 & U+11A55 & U+11A96)

- ^ 𑚈𑚫 (U+11688 & U+116AB)

- ^ ༀ (U+0F00)

- ^ 𑓇 (U+114C7)

- ^ ᬒᬁ (U+1B12 & U+1B01)

- ^ ဥုံ (U+1025 & U+102F & U+1036)

- ^ 𑄃𑄮𑄀 (U+11103 & U+1112E & U+11100)

- ^ ꨯꩌ (U+AA05 & U+AA4C)

- ^ ꨀꨯꨱꩌ (U+AA00 & U+AA2F & U+AA31 & U+AA4C)

- ^ 𑍐 (U+11350)

- ^ ꦎꦴꦀ (U+A98E & U+A980 & U+A9B4)

- ^ ಓಂ (U+0C93 & U+0C82)

- ^ ឱំ (U+17B1 & U+17C6)

- ^ ៚ (U+17DA)

- ^ ໂອໍ (U+0EAD & U+0EC2 & U+0ECD)

- ^ ഓം (U+0D13 & U+0D02)

- ^ ඕං (U+0D95 & U+0D82)

- ^ ௐ (U+0BD0)

- ^ ఓం (U+0C13 & U+0C02)

- ^ โอํ (U+0E2D & U+0E42 & U+0E4D)

- ^ ๛ (U+0E5B)

- ^ 唵 (U+5535)

- ^ 옴 (U+110B & U+1169 & U+1106)

- ^ オーム (U+30AA & U+30FC & U+30E0)

- ^ ᢀᠣᠸᠠ (U+1826 & U+1838 & U+1820 & U+1880)

- ^ އޮމ (U+0787 & U+07AE & U+0789)

- ^ 𑣿 (U+118FF)

- ^ Praṇava Upaniṣad in Gopatha Brāhmaṇa ane.ane.26 and Uṇādisūtra i.141/one.142

- ^ meet Pāṇini, Aṣṭādhyāyī vi.i.95

- ^ see Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad 8-12, equanimous in Classical Sanskrit, which describes Om as having three mātra s corresponding to the 3 letters a-u-m

- ^ in the early 19th-century manuscript to a higher place Om is written अउ३म् with "अउ" equally ligature equally in ॐ without chandrabindu

- ^ later called Shiva

- ^ this is a reference to the three major Vedic burn down rituals

- ^ this is a reference to the iii major Vedas

- ^ this is a reference to the three worlds of the Vedas

- ^ Sanskrit original, quote: द्वे वाव ब्रह्मणो रूपे मूर्तं चामूर्तं च । अथ यन्मूर्तं तदसत्यम् यदमूर्तं तत्सत्यम् तद्ब्रह्म तज्ज्योतिः यज्ज्योतिः स आदित्यः स वा एष ओमित्येतदात्माभवत् [68]

- ^ Hume translates this as "imperishable Brahma", Max Muller translates it as "indestructible Brahman"; see: Max Muller, The Upanishads, Function 2, Mundaka Upanishad, Oxford University Press, page 36

- ^ The Sanskrit word used is Vyadh, which means both "penetrate" and "know"; Robert Hume uses penetrate, but mentions the 2d meaning; see: Robert Hume, Mundaka Upanishad, 13 Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Printing, page 372 with footnote 1

- ^ Quote: "While Ek literally means One, Onkar is the equivalent of the Hindu "Om" (Aum), the one syllable sound representing the holy trinity of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva - the God in His entirety."[117]

- ^ Quote: "the 'a,' 'u,' and 'grand' of aum have likewise been explained every bit signifying the three principles of creation, sustenance and annihilation. ... aumkār in relation to existence implies plurality, ... simply its substitute Ik Onkar definitely implies singularity in spite of the seeming multiplicity of existence. ..."[119]

- ^ Quote: "Ik Aumkara is a significant proper name in Guru Granth Sahib and appears in the very starting time of Mul Mantra. It occurs as Aum in the Upanishads and in Gurbani, the Onam Akshara (the letter Aum) has been considered every bit the abstract of iii worlds (p. 930). Co-ordinate to Brihadaranyaka Upanishad "Aum" connotes both the transcendent and immanent Brahman."[121]

References [edit]

- ^ T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993), Elements of Hindu Iconography, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120808775, p. 248

- ^ Sehdev Kumar (2001), A Thousand Petalled Lotus: Jain Temples of Rajasthan, ISBN 978-8170173489, p. 5

- ^ Jan Gonda (1963), The Indian Mantra, Oriens, Vol. sixteen, pp. 244–297

- ^ a b Julius Lipner (2010), Hindus: Their Religious Behavior and Practices, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415456760, pp. 66–67

- ^ a b James Lochtefeld (2002), "Om", The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N-Z, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931804, page 482

- ^ a b Holdrege, Barbara A. (1996). Veda and Torah: Transcending the Textuality of Scripture. SUNY Printing. p. 57. ISBN978-0-7914-1640-ii.

- ^ "Om". Merriam-Webster (2013), Pronounced: \ˈōm\

- ^ a b c d Wilke, Annette; Moebus, Oliver (2011). Audio and Communication: An Artful Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 435. ISBN978-3110181593.

- ^ a b Krishna Sivaraman (2008), Hindu Spirituality Vedas Through Vedanta, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812543, page 433

- ^ a b David Leeming (2005), The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, Oxford University Printing, ISBN 978-0195156690, page 54

- ^ a b Hajime Nakamura, A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy, Role two, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120819634, page 318

- ^ a b c d e f g h Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus (2011), Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism, De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3110181593, pages 435–456

- ^ a b David White (2011), Yoga in Practice, Princeton University Printing, ISBN 978-0691140865, pp. 104–111

- ^ a b Alexander Studholme (2012), The Origins of Om Manipadme Hum: A Study of the Karandavyuha Sutra, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791453902, pages i–4

- ^ Misra, Nityanand (25 July 2018). The Om Mala: Meanings of the Mystic Sound. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 104–. ISBN978-93-87471-85-6.

- ^ "OM". Sanskrit English language Lexicon, University of Köln, Germany

- ^ James Lochtefeld (2002), Pranava, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N-Z, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931804, page 522

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 74-75, 347, 364, 667

- ^ Diana Eck (2013), Republic of india: A Sacred Geography, Random Business firm, ISBN 978-0385531924, folio 245

- ^ R Mehta (2007), The Phone call of the Upanishads, Motilal Barnarsidass, ISBN 978-8120807495, page 67

- ^ Omkara, Sanskrit-English Lexicon, Academy of Koeln, Federal republic of germany

- ^ CK Chapple, West Sargeant (2009), The Bhagavad Gita, Twenty-5th–Anniversary Edition, Land University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1438428420, page 435

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford Academy Printing, folio 12 with footnote 1

- ^ a b c Parpola, Asko (1981). "On the Chief Pregnant and Etymology of the Sacred Syllable ōm". Studia Orientalia Electronica. fifty: 195–214. ISSN 2323-5209.

- ^ Parpola, Asko (2015). The Roots of Hinduism : the Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. New York. ISBN9780190226909.

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, Oxford University Press, pages 1-21

- ^ a b Paul Deussen, 60 Upanishads of the Veda, Volume ane, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 67-85, 227, 284, 308, 318, 361-366, 468, 600-601, 667, 772

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 207

- ^ John Grimes (1995), Ganapati: The Vocal of Cocky, State Academy of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791424391, pages 78-80 and 201 footnote 34

- ^ Aitareya Brahmana five.32, Rig Veda, pages 139-140 (Sanskrit); for English translation: Come across Arthur Berriedale Keith (1920). The Aitareya and Kauṣītaki Brāhmaṇas of the Rigveda. Harvard University Press. p. 256.

- ^ a b Whitney, William Dwight (1950). Sanskrit Grammer: Including both the Classical Language, and the older Dialects, of Veda and Brahmana. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Academy Printing. pp. 12, 27–28.

- ^ Osho (2012). The Book of Secrets, unpaginated. Osho International Foundation. ISBN 9780880507707.

- ^ Mehta, Kiran Yard. (2008). Milk, Honey and Grapes, p.14. Puja Publications, Atlanta. ISBN 9781438209159.

- ^ Misra, Nityanand (2018). The Om Mala, unpaginated. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9789387471856.

- ^ Vālmīki; trans. Mitra, Vihārilāla (1891). The Yoga-vásishtha-mahárámáyana of Válmiki, Book 1, p.61. Bonnerjee and Visitor. [ISBN unspecified].

- ^ Kobayashi, Masato (2006). "Pāṇini's Phonological Rules and Vedic: Aṣṭādhyāyī 8.two*" (PDF). Journal of Indological Studies. eighteen: 16.

- ^ Joseph Campbell (1949), The Hero with a Thousand Faces, 108f.

- ^ Henry Parker, Aboriginal Ceylon (1909), p. 490.

- ^ HK Deb, Periodical of the Royal Asiatic Guild of Bengal, Book 17, Number 3, folio 137

- ^ The Swastika, p. PA365, at Google Books, Nature, Vol. 110, No. 2758, page 365

- ^ Ankita Roy (2011), Rediscovering the Brahmi Script. Industrial Design Heart, IIT Bombay. See the department, "Ancient Symbols".

- ^ SC Kak (1990), Indus and Brahmi: Further Connections. Cryptologia, xiv(two), pages 169-183

- ^ Deborah Wong (2001), Sounding the Center: History and Aesthetics in Thai Buddhist Functioning, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226905853, page 292

- ^ James Minahan (2009), The Consummate Guide to National Symbols and Emblems, ISBN 978-0313344961, pages 28-29

- ^ "ឱម: ប្រភពនៃរូបសញ្ញាឱម". Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "ឱម : អំណាចឱមនៅក្នុងសាសនា". Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "Om". 10 November 2020.

- ^ Ellwood, Robert S.; Alles, Gregory D. (2007). The Encyclopedia of World Religions. Infobase Publishing. pp. 327–328. ISBN9781438110387.

- ^ Beck, Guy L. (1995). Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Audio. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 42–48. ISBN9788120812611.

- ^ Monier Monier-Williams (1893), Indian Wisdom, Luzac & Co., London, page 17

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Printing, pages 1-3 with footnotes

- ^ a b c Paul Deussen, Lx Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 68-seventy

- ^ a b Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early on Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, page 171-185

- ^ Paul Deussen, 60 Upanishads of the Veda, Volume one, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 70-71 with footnotes

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Printing, pages iv-6 with footnotes

- ^ a b Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Printing, pages 178-180

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Office I, Oxford University Press, pages 4-nineteen with footnotes

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 28 with footnote ane

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 35

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 269-273

- ^ Max Muller (1962), Katha Upanishad, in The Upanishads – Part II, Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0486209937, page viii

- ^ a b Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Book one, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 284-286

- ^ a b c Muller, Max (ed.). The Upanishads: Maitrayana-Brahmana Upanishad. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 307–308.

- ^ Maitri Upanishad – Sanskrit Text with English Translation [ permanent dead link ] EB Cowell (Translator), Cambridge University, Bibliotheca Indica, page 258-260

- ^ Max Muller, The Upanishads, Part 2, Maitrayana-Brahmana Upanishad, Oxford University Press, pages 306-307 poesy 6.3

- ^ Deussen, Paul, ed. (1980). Lx Upanishads of the Veda. Vol. 1. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 347. ISBN978-8120814684.

- ^ Cowell, East.B. (ed.). Maitri Upanishad: Sanskrit Text with English Translation. Bibliotheca Indica. Translated by Cowell, East.B. Cambridge University Press. p. 258.

- ^ (in Sanskrit) – via Wikisource.

- ^ Paul Deussen (Translator), Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Vol two, Motilal Banarsidass (2010 Reprint), ISBN 978-8120814691, pages 580-581

- ^ Eduard Roer, Mundaka Upanishad [ permanent expressionless link ] Bibliotheca Indica, Vol. XV, No. 41 and 50, Asiatic Gild of Bengal, folio 144

- ^ Robert Hume, Mundaka Upanishad, Thirteen Master Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 372-373

- ^ Charles Johnston, The Mukhya Upanishads: Books of Hidden Wisdom, (1920–1931), The Mukhya Upanishads, Kshetra Books, ISBN 978-1495946530 (Reprinted in 2014), Annal of Mundaka Upanishad, pages 310-311 from Theosophical Quarterly journal

- ^ Mundaka Upanishad, in Upanishads and Sri Sankara'south commentary – Book 1: The Isa Kena and Mundaka, SS Sastri (Translator), University of Toronto Archives, page 144 with section in 138-152

- ^ a b c d e f Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume two, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814691, pages 605-637

- ^ a b c d eastward f g Hume, Robert Ernest (1921), The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford Academy Printing, pp. 391–393

- ^ Charles Johnston, The Measures of the Eternal – Mandukya Upanishad Theosophical Quarterly, October, 1923, pages 158-162

- ^ Paul Deussen, Lx Upanishads of the Veda, Volume one, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 308

- ^ Max Muller, Shvetashvatara Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part Ii, Oxford University Press, page 237

- ^ Robert Hume (1921), Shvetashvatara Upanishad one.xiv – 1.16, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 396-397 with footnotes

- ^ Grimes, John A. (1995). Ganapati: Song of the Self. State University of New York Printing. pp. 77–78. ISBN978-0-7914-2439-1.

- ^ Alter, Stephen (2004). Elephas Maximus: a portrait of the Indian Elephant. New Delhi: Penguin Books. p. 95. ISBN978-0143031741.

- ^ Grimes (1995), pp. 23–24.

- ^ Saraswati (1987), p. 127, In Chinmayananda's numbering system, this is upamantra 8.

- ^ "Valmiki Ramayana - Yuddha Kanda - Sarga 117".

- ^ a b Jeaneane D. Fowler (2012), The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845193461, folio 164

- ^ Mukundananda (2014). "Bhagavad Gita, The Song of God: Commentary by Swami Mukundananda". Jagadguru Kripaluji Yog.

- ^ a b Jeaneane D. Fowler (2012), The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845193461, folio 271

- ^ Translator: KT Telang, Editor: Max Muller, The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita at Google Books, Routledge Print, ISBN 978-0700715473, page 120

- ^ The Vishnu-Dharma Vidya [Chapter CCXXI]. 16 April 2015.

- ^ "14, King Purūravā Enchanted past Urvaśī". Bhāgavata Purāṇa, Canto 9. Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, Inc.

- ^ Guy Beck (1995), Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812611, page 154

- ^ Rocher, Ludo (1986). The Purāṇas. Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz. ISBN978-3447025225.

- ^ "Adi Parashakti - The Divine Mother". TemplePurohit - Your Spiritual Destination Bhakti, Shraddha Aur Ashirwad. 1 Baronial 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Swami Narayanananda (1960). The Key Ability in Man: The Kundalini Shakti. Health Inquiry Books. ISBN9780787306311.

- ^ a b The Yogasutras of Patanjali Charles Johnston (Translator), page 15

- ^ "Indian Century - OM". www.indiancentury.com.

- ^ Kaviraja, Krishnadasa (1967). "xx, the Goal of Vedānta Study". Teachings of Lord Caitanya. Translated by A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Bhaktivedanta Volume Trust International, Inc.

- ^ a b Von Glasenapp (1999), pp. 410–411.

- ^ Om – significance in Jainism, Languages and Scripts of India, Colorado Land University

- ^ "Namokar Mantra". Digambarjainonline.com. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ Samuel, Geoffrey (2005). Tantric Revisionings: New Understandings of Tibetan Buddhism and Indian Religion. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN9788120827523.

- ^ "Vajrayana Buddhism Origins, Vajrayana Buddhism History, Vajrayana Buddhism Beliefs". www.patheos.com . Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ ""OM" - THE SYMBOL OF THE ABSOLUTE". Retrieved xiii Oct 2015.

- ^ Olsen, Carl (2014). The Different Paths of Buddhism: A Narrative-Historical Introduction. Rutgers University Printing. p. 215. ISBN978-0-8135-3778-8.

- ^ Getty, Alice (1988). The Gods of Northern Buddhism: Their History and Iconography . Dover Publications. pp. 29, 191–192. ISBN978-0-486-25575-0.

- ^ Gyatso, Tenzin. "On the significant of: OM MANI PADME HUM - The jewel is in the lotus or praise to the jewel in the lotus". www.sacred-texts.com . Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ C. Alexander Simpkins; Annellen M. Simpkins (2009). Meditation for Therapists and Their Clients. Westward.W. Norton. pp. 159–160. ISBN978-0-393-70565-two.

- ^ C. Alexander Simpkins; Annellen M. Simpkins (2009). Meditation for Therapists and Their Clients. W.W. Norton. p. 158. ISBN978-0-393-70565-two.

- ^ a b Snodgrass, Adrian (2007). The Symbolism of the Stupa, Motilal Banarsidass. p. 303. ISBN978-8120807815.

- ^ a b Baroni, Helen J. (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism. Rosen Publishing. p. 240. ISBN978-0-8239-2240-vi.

- ^ a b c ""A united nations" (阿吽)". Japanese Architecture and Art Internet Users System. 2001. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ Daijirin Japanese dictionary, 2008, Monokakido Co., Ltd.

- ^ Komainu and Niô Dentsdelion Antiques Tokyo Newsletter, Volume 11, Part iii (2011)

- ^ Brawl, Katherine (2004). Brute Motifs in Asian Art. Dover Publishers. pp. 59–sixty. ISBN978-0-486-43338-7.

- ^ Arthur, Chris (2009). Irish Elegies. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 21. ISBN978-0-230-61534-2.

- ^ a b c Doniger, Wendy (1999). Merriam-Webster'due south encyclopedia of world religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 500. ISBN978-0-87779-044-0 . Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ a b Mahinder Gulati (2008), Comparative Religious And Philosophies : Anthropomorphlsm And Divinity, Atlantic, ISBN 978-8126909025, pages 284-285

- ^ Singh, Khushwant (2002). "The Sikhs". In Kitagawa, Joseph Mitsuo (ed.). The religious traditions of Asia: religion, history, and culture. London: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 114. ISBN0-7007-1762-v.

- ^ a b Singh, Wazir (1969). Aspects of Guru Nanak's philosophy. Lahore Book Shop. p. 20. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ^ a b Pashaura Singh (2014), in The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies (Editors: Pashaura Singh, Louis E. Fenech), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199699308, page 227

- ^ a b Kohli, S.Due south. (1993). The Sikh and Sikhism. Atlantic. p. 35. ISBN81-71563368.

- ^ Singh, Wazir (1969). "Guru Nanak's philosophy". Journal of Religious Studies. i (one): 56.

- ^ "Liber Samekh". www.sacred-texts.com . Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Magick in Theory and Exercise - Chapter 7". world wide web.sacred-texts.com . Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Crowley, Aleister (1997). Magick : Liber ABA, volume iv, parts I-IV (2d revised ed.). San Francisco, CA. ISBN9780877289197.

- ^ Crowley, Aleister (2016). Liber XV : Ecclesiae Gnosticae Catholicae Canon Missae. Gothenburg. ISBN9788393928453.

- ^ Messerle, Ulrich. "Graphics of the Sacred Symbol OM". Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved xiv January 2019.

- ^ Kumar, Southward.; Nagendra, H.R.; Manjunath, N.Thousand.; Naveen, Grand.5.; Telles, S. (2010). "Meditation on OM: Relevance from ancient texts and contemporary science". International Journal of Yoga. 3 (1): ii–5. doi:10.4103/0973-6131.66771. PMC2952121. PMID 20948894. S2CID 2631383.

Bibliography [edit]

- Francke, A. H. (1915). "The Meaning of the "Om-mani-padme-hum" Formula". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Guild of Not bad U.k. and Republic of ireland: 397–404. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00048425. JSTOR 25189337.

- Gurjar, A. A.; Ladhake, S. A.; Thakare, A. P. (2009). "Assay of Acoustic of "OM " Dirge to Study It's [sic] Issue on Nervous System". International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security. 9 (i): 363–367. CiteSeerX10.1.1.186.8652.

- Kumar, S.; Nagendra, H.; Manjunath, Northward.; Naveen, K.; Telles, S. (2010). "Meditation on OM: Relevance from aboriginal texts and contemporary science". International Journal of Yoga. three (i): 2–5. doi:ten.4103/0973-6131.66771. PMC2952121. PMID 20948894.

- Kumar, Uttam; Guleria, Anupam; Khetrapal, Chunni Lal (2015). "Neuro-cognitive aspects of "OM" sound/syllable perception: A functional neuroimaging written report". Cognition and Emotion. 29 (3): 432–441. doi:10.1080/02699931.2014.917609. PMID 24845107. S2CID 20292351.

- Saraswati, Chinmayananda (1987). Glory of Ganesha. Bombay: Central Chinmaya Mission Trust. ISBN978-8175973589.

- Stein, Joel (4 August 2003). "Simply say Om" (PDF). Fourth dimension Magazine.

- Telles, Southward.; Nagarathna, R.; Nagendra, H. R. (1995). "Autonomic changes during "OM" meditation" (PDF). Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 39 (4): 418–420. ISSN 0019-5499. PMID 8582759.

- Vivekanda. – via Wikisource.

- Von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1999). Der Jainismus: Eine Indische Erlosungsreligion [Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation] (in German). Shridhar B. Shrotri (trans.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN81-208-1376-six.

Source: https://wiki.alquds.edu/?query=Om

0 Response to "Art Final Quizlet Great Stupa India Picture Angkor Wat Cambodia"

Post a Comment